Mental Health, Wellness, and COVID-19

by Alexis Wing and Gracie Rolfe, MSW

Health Resources in Action

The ways that we view and discuss mental health in our society have transformed significantly over the last several decades. Once widely considered taboo and ostracizing, countless efforts have been made to destigmatize conversations around mental healthwhich now appear routinely in mainstream media and are beginning to become normalized in everyday interactions. Public health practitioners continue to emphasize mental health as a critical component of overall health and wellbeing. While we aware of the tragic impact that the COVID-19 pandemic over the last year has had on folks’ physical health, it is also important to recognize how the last year has dramatically impacted people’s mental health in several ways, including loss of employment, isolation, loss of loved ones, loss of community resources, and countless others. We also know that the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC).

Impact of COVID-19 on BIPOC

Due to the impacts of centuries of structural and systemic racism and generational trauma, BIPOC are more susceptible than their White counterparts to contract COVID-19. BIPOC are also more likely to experience the ramifications of COVID-19 external to physical health, such as loss of employment, lack of access to equitable health care, and difficulties in maintaining supportive housing – all factors and determinants we know play a tremendously important role in not only supporting physical health but mental health and wellness as well. Below are some statistics that illustrate the stark relevance of COVID-19 in BIPOC communities:

- Black people make up 13-15% of the United States population, but about 27% of COVID-19 cases in the US. This doesn’t account for the 14+ %of cases among people who identified themselves as “multiple” or “other.” (Cohut, 2020).

- Black Americans are dying from COVID-19 at nearly 2.5 times the rate of white people (61.6 deaths compared to 26.2 deaths per 100,000 people). This is the highest mortality rate of any racial/ethnic group and, since data started being reported, has consistently been over twice as high as any other group (APM Research Lab, 2020).

- About 11.9% of employees in the US are Black, but they make up 17% of “front-line” (essential) workers, further increasing the disproportionately high rates of COVID-19 infection and death (Smialek and Takersely, 2020).

- The Navajo Nation has the highest infection rate of COVID-19 per capita in the U.S. when compared with any individual state (Cheetham, 2020).

- Nearly half (49%) of the Latinx population say they or someone in their household had to take a pay cut or lost their job (or both) due to COVID-19, compared to 33% of all US adults (Morales, 2020).

- The Latinx demographic in the US largely works in essential and service jobs; due to COVID-19, these industries either crashed (like the hotel/travel industry) leading to lost jobs or required employees to be on the front lines and risk infection (workplaces like hospitals and grocery stores) (Morales, 2020).

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has turned down a series of requests from tribal epidemiology centers for COVID-19 data – the same data that is freely available to states. Without this data, tribal authorities can’t initiate contact tracing on their lands or impose informed lockdowns or other restrictions (Tahir and Cancryn, 2020).

- Racist physical and verbal attacks on Asian and Pacific Islander people have spiked worldwide since the start of COVID-19 outbreaks (Human Rights Watch, 2020).

The detrimental impacts that COVID-19 has had on BIPOC and their mental health has also been compounded by the recent global reckoning of the systems that perpetuate racism and continue to uphold white supremacy culture. Many communities, both across the United States and globally, were galvanized in support of Black lives after the events of this past summer, in which several Black Americans were killed at the hands of the police. The combined impacts of these events further underscores the need for adequate, culturally responsive, and accessible mental health services for BIPOC.

Drug Use, Sobriety, Recovery, and COVID-19

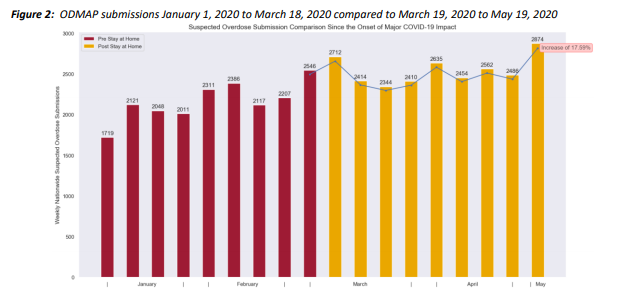

We also recognize that this time has been especially challenging for people in early recovery, early sobriety, and those actively using drugs, who often already experience marginalization due the pervasive stigma associated with drug use. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of June 2020, 13% of Americans reported starting or increasing substance use as a way of coping with stress or emotions related to COVID-19. Drug-related overdoses have also spiked since the onset of the pandemic. A reporting system called ODMAP shows that the early months of the pandemic brought an 18% increase nationwide in overdoses compared with those same months in 2019. The trend has continued throughout 2020, which reported in December that more than 40 U.S. states have seen increases in opioid-related mortality along with ongoing concerns for those with substance use disorders (Abramson, 2021).

We know that connection and fostering community is an essential component for people, particularly in this community. A foundational principal of working with and engaging people who are using drugs and/or living with a substance use disorder is rooted in connection, community, and communication. We encourage community coalitions, community organizations, and other entities to share resources for people who are actively using drugs or may be struggling in recovery. The Massachusetts Substance Use Helpline, in addition to the Vermont Helplink, and the Illinois Helpline for Opioids and Other Substances, are free and accessible resources to people living in these states who wish to gain more information and assistance with accessing substance use treatment, harm reduction, and other recovery resources.

Moving Away from Self-Care and Towards Community and Structural Care.

Often, a regularly prescribed antidote to supporting mental wellness is practicing self-care. While we acknowledge that self-care and self-soothing practices, such as exercise, napping, or binge-watching TV, can be beneficial by allowing us to take a break and revitalize ourselves, they are often not sustainable in the long run to support and uplift people’s mental health and wellness. This is because the systems and structures that we work and live within are not designed to support people’s mental health. Structural issues like an unlivable minimum wage, inadequate housing, lack of access to childcare, lack of access to affordable health care, and food apartheids (which are often responsible for poor mental health) require structural and systemic responses and cannot only be mitigated by self-care and self-soothing practices: we need more structural interventions. For this reason, community care, defined as giving and receiving care in ways that support shared wellbeing and connectedness, particularly amidst shared struggles, can be a more practical approach.

There are policies and practices that public health practitioners and community coalitions can advocate for to uplift community care, such as adequate paid time off (and incentives/encouragement to take this time off), paid maternity/paternity leave, access to quality and affordable health care (including therapy and other professional supports), supportive supervision, and flexible work from home policies. Resources such as community food pantries and fridges, and mutual aid groups can also be powerful tools to uplift community care. Acknowledging that maintaining and uplifting mental wellness is not only on us is important to broadening the discussion around mental health and continuing to push forward structural changes that can support community care and mental health in the long run. At Health Resources in Action, we deeply explore this topic of community care and accountability in our training titled “Secondary Trauma and Helping Professionals.” We invite all relevant providers to take part in this free training, as we explore the effects of secondary trauma, brainstorm best practices around self-care, and envision a future where people and societies are supported through structural and community care.

Conclusion

We value and recognize the deep-rooted importance of supporting and nurturing mental health and wellness. As our society moves towards de-stigmatizing mental health and wellness, we challenge corporations, organizations, and other entities to take a hard look at their internal policies, structures, protocols, and systems to see if they align with uplifting and supporting the mental health and wellness of their workers and employees. We know that when our mental health is supported and valued, we can contribute in extraordinary ways, both in our personal and professional lives. It is long past time to fund, value, appreciate and de-stigmatize topics of mental health and wellness!

CITATIONS:

Abramson, A. (2021). Substance use during the pandemic: Opioid and stimulant use is on the rise – how can psychologists and other clinicians helps a greater number of patients struggling with drug use? Vol. 52 No. 2. Retrieved from: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2021/03/substance-use-pandemic

APM Research Lab. (2020, June 10). The color of coronavirus: COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity in the U.S. https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race

Cheetham, J. (2020, June 16). Navajo Nation: The people battling America’s worst coronavirus outbreak. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52941984

Cohut, M. (2020, May 18). COVID-19: The mental health impact on people of color and minority groups. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/covid-19-mental-health-impact-on-people-of-color-and-minority-groups

Human Rights Watch. (2020, May 12). COVID-19 fueling anti-Asian racism and xenophobia worldwide. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/12/covid-19-fueling-anti-asian-racism-and-xenophobia-worldwide

Morales, E. (2020, May 18). Understanding why Latinos are so hard hit by COVID-19. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/18/opinions/latinos-covid-19-impact-morales/index.html

Price, J.H., Khubchandani, J., McKinney, M., & Braun, R. (2013). Racial/ethnic disparities in chronic diseases of youths and access to health care in the United States. BioMed Research International, 787616. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3794652/#

Smialek, J. & Tankersley, J. (2020, June 2). Black workers, already lagging, face big economic risks. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/01/business/economy/black-workers-inequality-economic-risks.html

Tahir, D. & Cancryn, A. (2020, June 11). American Indian tribes thwarted in efforts to get coronavirus data. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/06/11/native-american-coronavirus-data-314527