Author: Tonayo Crow

This year, the American Lung Association chose Air Pollution and Health as their theme of 2019, using the last twelve months to highlight different topic areas within this overarching theme, including where air pollution comes from, who bears the burden, and how we can empower youth to fight for clean air. With only weeks left until 2020 arrives, now is the perfect time to reflect on and highlight this important topic. Air is a vital and communal human resource, yet millions of people live in places with harmful levels of air pollution. It is not uncommon to read about cities that are forced to close schools and workplaces due to poor air quality, or to see images in the news of dense smog hovering over a cityscape. This threat to human health, ironically, emerged in the wake of industrialism and the increased use of fossil fuels (e.g. coal, oil, natural gas) to power human industry and urban life. The good news? Humans created the problem of air pollution, so we have the power to manage and reduce its impacts.

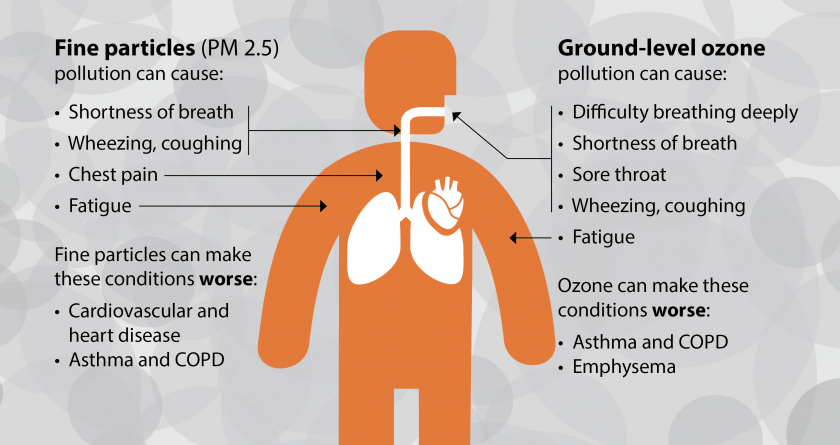

In the US, air po llution is (unsurprisingly) worse in bigger cities (e.g. Los Angeles, Chicago, Phoenix), and climate change only compounds the impacts of air pollution. For example, more extreme heat in the summer for longer periods of time increases levels of particulate matter and ozone (a major component of smog) in the air, and the increased number of wildfires in recent years has created more opportunity for respiratory irritation, asthma, and allergies. With scientists urging immediate action, a sense of urgency and desperation often accompanies discussions of curbing the worst effects of climate change. The threat looms especially large for low income communities and communities of color, which are often located nearest to environmental hazards and face chronic environmental injustices. This is exemplified by Chelsea, MA, where 21% of residents are below the poverty line and 60% identify as Hispanic or Latino (as of 2017). Chelsea is at the forefront of a battle against air pollution in their community: the jet fuel for Boston Logan Airport is stored on the water in Chelsea, and there are frequent emissions from delivery trucks that come in and out of a New England produce center. And as sea levels rise, Chelsea faces increased risks of flooding and damage from the creeks and waterways that border the city. There is no way to talk about air pollution without talking about health inequities and environmental injustice. The bright spot, however, is the work that people are already doing to protect our air and provide better health outcomes for everyone.

llution is (unsurprisingly) worse in bigger cities (e.g. Los Angeles, Chicago, Phoenix), and climate change only compounds the impacts of air pollution. For example, more extreme heat in the summer for longer periods of time increases levels of particulate matter and ozone (a major component of smog) in the air, and the increased number of wildfires in recent years has created more opportunity for respiratory irritation, asthma, and allergies. With scientists urging immediate action, a sense of urgency and desperation often accompanies discussions of curbing the worst effects of climate change. The threat looms especially large for low income communities and communities of color, which are often located nearest to environmental hazards and face chronic environmental injustices. This is exemplified by Chelsea, MA, where 21% of residents are below the poverty line and 60% identify as Hispanic or Latino (as of 2017). Chelsea is at the forefront of a battle against air pollution in their community: the jet fuel for Boston Logan Airport is stored on the water in Chelsea, and there are frequent emissions from delivery trucks that come in and out of a New England produce center. And as sea levels rise, Chelsea faces increased risks of flooding and damage from the creeks and waterways that border the city. There is no way to talk about air pollution without talking about health inequities and environmental injustice. The bright spot, however, is the work that people are already doing to protect our air and provide better health outcomes for everyone.

One comprehensive approach to tackling air pollution is cross-sector collaboration. For example, the Massachusetts Asthma Action Partnership (MAAP) works across state agencies, health and human service organizations, health care providers, and housing and education stakeholders to improve the quality of life of folks living with asthma. Asthma is linked intimately to air quality and climate change, since longer periods of heat correlate with increased amounts of respiratory irritants, which aggravate asthma symptoms. And as mentioned above, asthma is another example of how air pollution must be viewed through a health equity lens. In Massachusetts, Black, non-Hispanic folks have higher rates of asthma than White, non-Hispanic people, and are more likely to end up hospitalized from asthma complications. In order to reduce these inequities, the work of groups like MAAP is essential in demonstrating how working across sectors allows people to harness the power of many institutions, bolstering the chance for a lasting impact.

In addition, cities across Massachusetts are taking ownership of the fight for cleaner air. For instance, Springfield, MA won a grant this summer for their plan to increase climate resiliency. Part of this policy includes building the capacity of residents to take action for climate change and educating residents on the health equity impacts of the climate crisis. The Springfield plan revolves around the reduction of greenhouse gases, including ozone, which impact air quality and human health. If every city and town in Massachusetts made a similar plan, the synergistic impact would be monumental.

There are also ways to fight for clean air on an individual level. Reduce your contribution to greenhouse gas emissions by conserving energy at home; ride a bike or take public transportation to work; buy environmentally friendly cleaning products; and compost at home (or introduce it at work!) Remember to also take preventative measures on days when air quality is low: check out airnow.gov for updated information on the air quality in your neighborhood, and do your best to limit your time outside when the Air Quality Index (AQI) is high. With this said, it is worth noting that public health strives to take an upstream approach to health, meaning we want to tackle the root causes of issues (e.g. systems that are inequitable or racist), rather than cast the blame on individuals or communities. The advice above is meant to be preventative, but it is not the solution. The solution will come when systems-level change happens, when communities do not face worse health outcomes due to their racial makeup or socioeconomic levels. We will have cleaner air when there is broad institutional backing from federal, state, and local governments. Until then, we must support the efforts of communities and organizations that have taken on this fight.

Finally, remember that there is power in voting, and lobbying your representatives to uphold legislation and research that protects this essential resource. As the year rolls to a close, please consider: what will you do to protect our air and our health?

References:

Air Now. “Current AQI.” Accessed December 3, 2019. https://airnow.gov/.

American Lung Association. “EPA’s ‘Censoring Science’ Rule Would Permanently Pollute Our Air and Harm Americans’ Health.” Accessed December 5, 2019. https://www.lung.org/our-initiatives/healthy-air/outdoor/fighting-for-healthy-air/healthy-air-resources/epas-censoring-science-rule.html.

American Lung Association. “Most Polluted Cities.” Accessed December 7, 2019. https://www.lung.org/our-initiatives/healthy-air/sota/city-rankings/most-polluted-cities.html.

American Lung Association. “Year of Air Pollution & Health 2019.” Accessed December 3, 2019. https://www.lung.org/our-initiatives/healthy-air/outdoor/fighting-for-healthy-air/year-of-air-pollution-and-health/.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. “Climate Change Decreases the Quality of the Air We Breathe.” Accessed December 7, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/pubs/AIR-QUALITY-Final_508.pdf.

Dooling, Shannon. “‘Hit First And Worst’: Region’s Communities Of Color Brace For Climate Change Impacts.” WBUR News, July 26, 2017. https://www.wbur.org/news/2017/07/26/environmental-justice-boston-chelsea.

Fountain, Henry. “Climate Change Is Accelerating, Bringing World ‘Dangerously Close’ to Irreversible Change.” New York Times, December 4, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/04/climate/climate-change-acceleration.html.

Massachusetts Asthma Action Partnership. “Get to know MAAP.” Accessed December 10, 2019. https://www.maasthma.org/overview.

Mass.gov. “Statistics About Asthma.” Accessed December 16, 2019. https://www.mass.gov/service-details/statistics-about-asthma.

Public Health Institute of Western Massachusetts. “Kresge Foundation awards $100,000 grant to the Public Health Institute of Western Massachusetts to build climate resilience, improve health.” Accessed December 11, 2019. https://www.publichealthwm.org/application/files/9115/6701/8244/press_release_Kresge_CCHE_PHIWM.pdf.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. “Actions You Can Take to Reduce Air Pollution.” Accessed December 10, 2019. https://www3.epa.gov/region1/airquality/reducepollution.html.